Views from the Speculator Mine Memorial: a silhouetted headframe.

“Butte has a bad reputation,” said Jim Hope midway through a tour at Headframe Spirits. He wanted his Saturday evening tour group to know that Butte’s notoriety— as a surly, down-on-its-luck community—isn’t fair.

Just a few hours later, Ted Ackerman, owner of the Miner’s Boutique Hotel, made the same point. Earlier that night, Ackerman had been at a fundraiser for the Muddy Creek Brewery, which was destroyed by a fire in January. The fundraiser’s location? “Butte Brewing Company,” Ackerman said. “A competitor.”

Having visited Butte for the Edible Bozeman Spring 2020 road trip, I want to wholeheartedly recommend it. But I can’t do so without recognizing a particular subtext we encountered there: The people we met in Butte weren’t looking to sell the place. They only wanted to make sure we learned what it is, because a lot of people have it wrong.

I won’t even try for a fair summary of Butte’s history. I mean, the town’s Wikipedia page reads like an ambitious television series proposal, zipping through an extensive network of copper mines, union labor riots, a brothel that operated for a century, a ninety-foot statue of the Virgin Mary, and, oh, Evel Knievel. Toss in a historic (and horrifying) mining disaster, pork chop sandwiches, and large-scale environmental cleanup efforts, and you can see I’d hardly know where to start.

The feel of history—that prominent melding of periods— is reflected in the town’s food, drink, and lodging options. The Miner’s Boutique is in a recently renovated building that still feels true to its 1913 construction even as it sports bold colors, murals of historical photographs, and remodeled bathrooms. Down the street there’s the Finlen, a hotel that opened in 1924 and has hosted the likes of John Kennedy and Charles Lindbergh. Now, the Finlen has a proud, well-maintained period vibe.

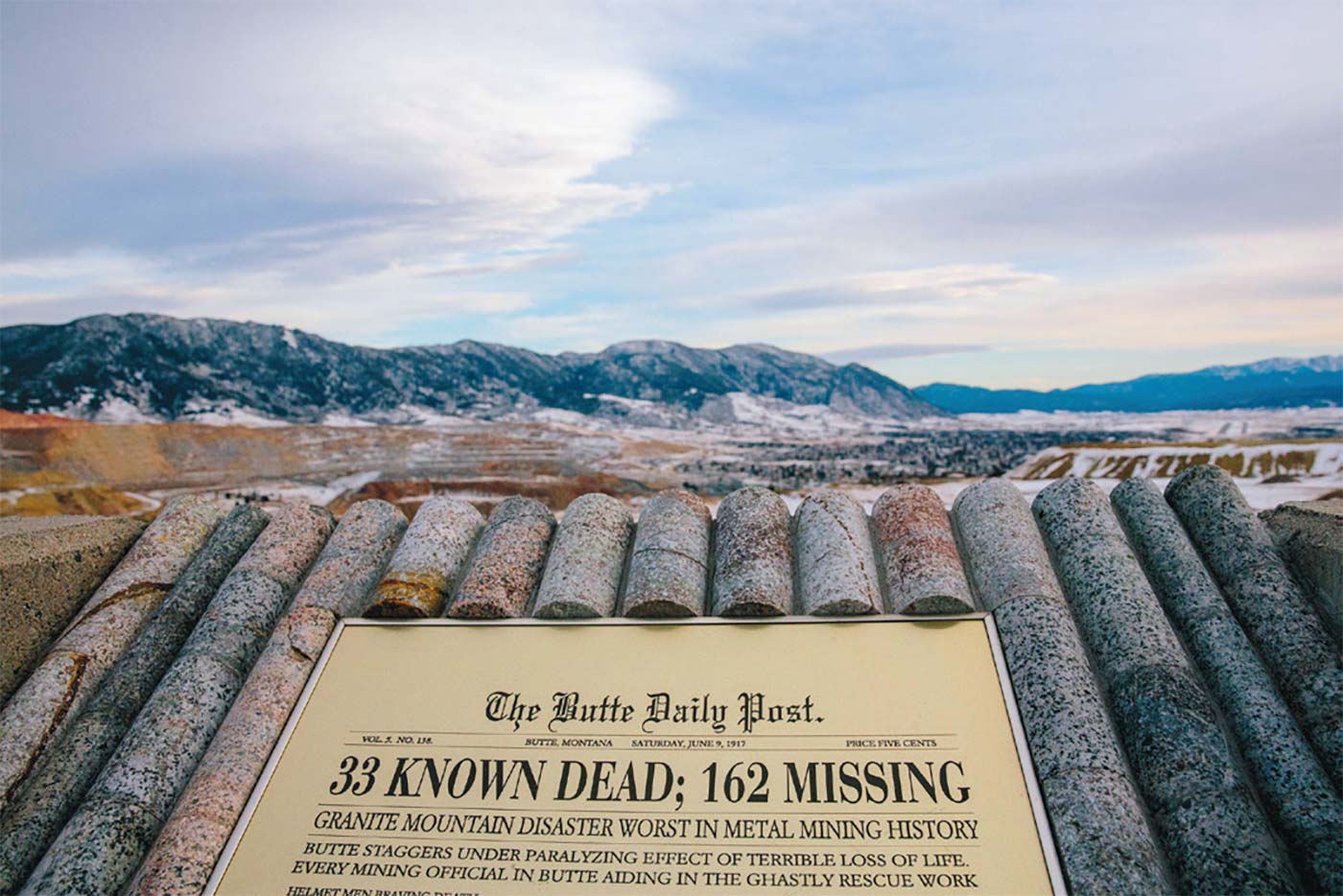

After a comfortable night in the Miner’s Boutique, we opted for coffee at Oro Fino, a modern, minimalist-inspired spot attached to a community art and resource center. Post-coffee, our slow morning turned into an increasingly slow midday jog up paved paths to the Speculator Mine Memorial, which commemorates the aforementioned disaster. Butte is built on the side of a hill, atop what is basically a huge pile of granite. Because of this geography, what most of us would call “downtown” is known, in Butte, as “uptown.” And uphill from “uptown” is even more hillside dotted with houses and old headframes. At the top stands the memorial, whose views are remarkable and humbling: there’s the grandeur of the distant mountains, the southerly sprawl past the (up/down) town, and to the southeast the yawning Berkeley Pit.

By the time we got back to town, I was windblown and hungry. Fortunately for me, we made it to Joe’s Pasty Shop before it closed. I’ve never been much of a pasty fan, though my spouse, who accompanied me on this trip, is a Wisconsinite who has strong (read: positive) feelings for the dish, which is usually some variation of meat and vegetables folded into a pastry. But this beef-and-potato pasty was—I do not exaggerate—so good it turned me into a pasty convert. It was perfectly hot and perfectly peppered, wrapped in a dough that had a nice crust but didn’t crumble. It was a bite of the past, literally, since the recipe is over seventy years old.

Hours later, we stood on the tiled floor of a renovated Buick showroom, now the distillery portion of Headframe Spirits. (Free tours are at 5:30 on Fridays and Saturdays and come with free samples.) My favorite was the Neversweat Bourbon Whiskey, named for a mine that was, by reputation, cooler than the others. Happy with our drinks and the tour, we headed to Park 217 for dinner, where our favorite appetizer was the bison and pork meatballs and the entrée of the night was my spouse’s pork chop with a pleasantly balanced huckleberry sauce. Exceptional service and eclectic range of well-executed dishes aside, Park 217 is worth a visit because of its setting, the basement of a tastefully renovated building, with exposed stone walls, wine alcove, and—look up when you enter—old-fashioned, two-bladed fans running on a pulley system.

Our last stop of the night was 51 Below, the speakeasy in the basement of the Miner’s Boutique. We meant to take a quick peek inside, but that proved impossible—everything about the speakeasy, from its clever rotary-phone-activated entrance to its gorgeous copper bar to its noisy welcome, kept us for another leisurely round of drinks.

In the morning, looking to avoid the worst of a snowstorm on our way out of town, we were some of the first guests to arrive at the Hummingbird Café, which offers locally made desserts and a rare (for Butte) array of vegetarian and vegan options. My spouse drove carefully on the way out of town. The roads were slick; we passed a truck that had slid off the road and into a trailer. And just like that—too soon, it seemed—we were past city limits and on our way home.

I think more people should visit Butte, but only partly so that the tough-town reputation can be dispelled, or at least complicated, by encountering the current iteration of a city that was, at the outset of the twentieth century, the largest city between the Mississippi River and San Francisco. Maybe I’m compelled to suggest Butte as a sort of civics- lesson destination, since the union history in the town is as long and storied as it is essential and complex. Maybe I think it would be good for most of us to stand at the edge of the Berkeley Pit with a combination of awe and dismay at the scope of our material needs, real or perceived. But maybe, most of all, I think I’m not alone in being drawn to once-booming towns with down-and-out pasts and futures being creatively and continually carved out by a community that just won’t quit.