An Evening with Anna Borgman

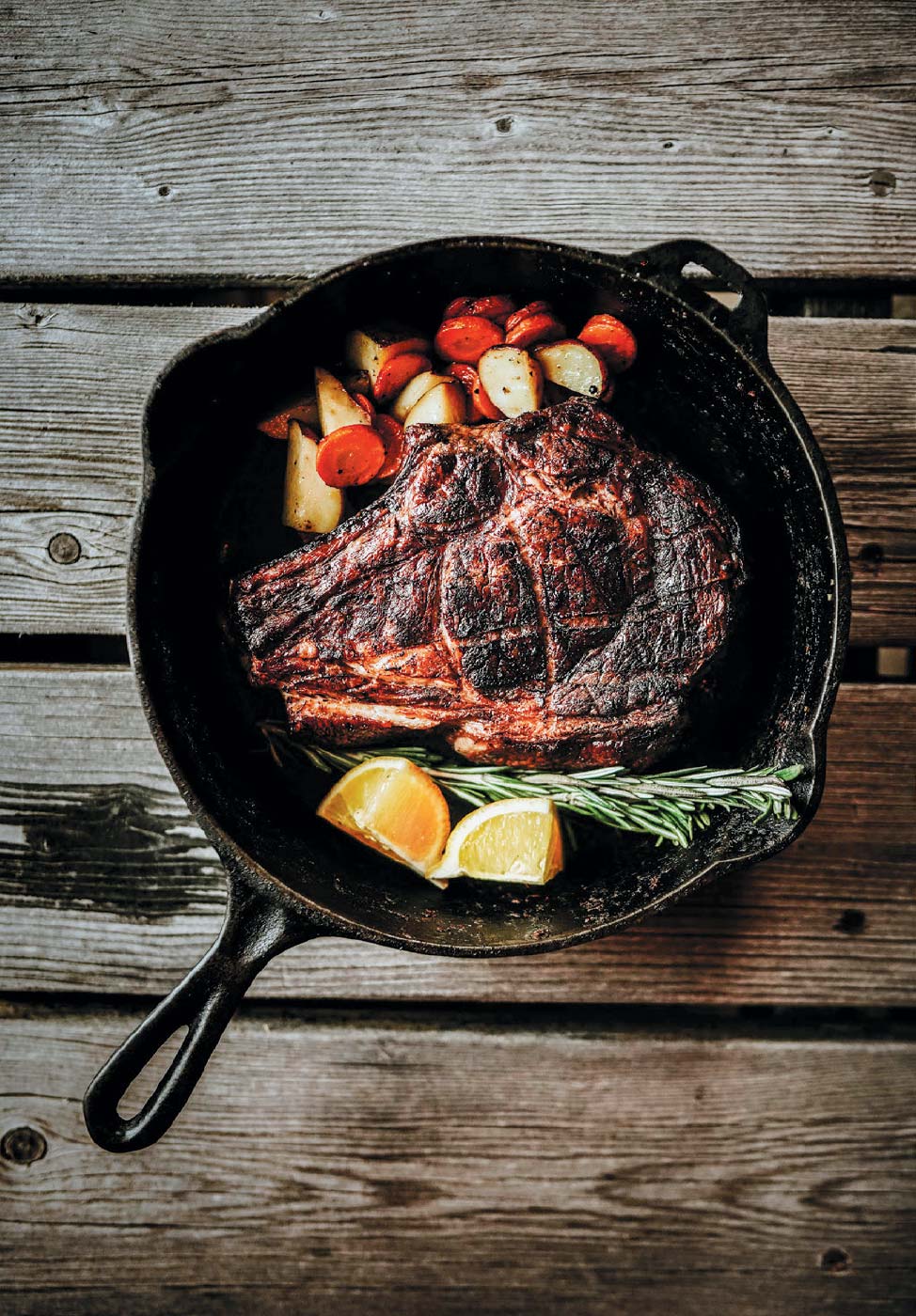

On a sunny winter day, with fresh snow in the mountains, some friends and I followed a winding road up to a quaint cabin, where Anna Borgman would be introducing her line of classes on butchery, bread-making, natural wine, and fermentation. We gathered around the large butcher-block counter and laid out our offerings: a slab of bone-in beef ribs from Boyd’s Cottonwood Ranch; goat cheese from Amaltheia Dairy; local carrots, potatoes, oyster mushrooms, and microgreens; fresh-baked bread from Wild Crumb; Montana lake trout that had been smoked the night before; and an assortment of natural wines, courtesy of Anna.

The sounds of laughter, knives chopping veggies, and mushrooms sizzling on the stove filled the kitchen. Anna showed us where the cut of beef came from on the cow, gesturing to her own ribs as a visual, and how it differs from other animals she butchers in her classes, such as lamb or goats.

Like many people in southwest Montana, I feel connected to the land and know many of the trails, streams, and a few secret mushroom spots. However, it really ends there. Do I know if those sheep in the field are heritage breed, and best for this climate? Do I know what flora cattle eat on the hillsides? Could I forage for plants along the creek? Do I know anything about which strains of wheat are better for our bodies and grow well in Montana? No.

It was a shared sentiment around the kitchen, but, thankfully, Anna told us that no one should be shamed for not knowing about their food systems; learning about food is an immense amount of work. Her mission as a teacher is to invoke the philosopher Epicurus, who believed we should live a pleasurable, simple life, surrounded by friends.

Anna grew up in Powell Butte, a tiny town in central Oregon with not much more than a post office, a school, and a country store. With her three siblings she ran around the endless BLM land surrounding the town. When her best friend, who lived on a farm, started raising sheep at a young age, Anna decided she wanted to do the same. Her parents helped build a tiny corral in their backyard and Anna’s interest in agriculture began. She joined 4-H at eight (her group was named The Wonderful Woolies) and maintained her focus through culinary school and earning a master’s in food systems and social justice. She is now working on a master’s certificate in natural resource policy. Instead of seeing just one right answer to food insecurity or environmental issues, as so many trends promise, Anna sees a complex interconnected web.

“I want people to understand the social, ecological, and economic impacts of their food choices,” she says. “It’s about changing our relationship to where we live, and seeing that food is all around us.” She does not pretend this is an easy job; in fact, Anna’s academic and field studies have taught her the opposite. Since about the second half of the twentieth century, when efficiency and automation became major goals of farming and ranching, we have created an interdependent food system that continues to stray from what’s natural and healthy for the land and our bodies. Anna stays hopeful, though, believing it is never too late to question our systems and make small changes.

We continued to prepare the food for our winter feast as Anna told stories about local farmers and ranchers she had met, what our food animals eat, and how it all affects our bodies. She spoke passionately about the cyclical nature of ecosystems—how it’s about the relationships we have with the land, with our farmers and ranchers, with the food we eat, and with each other that have the biggest impact on our food systems and the environment. She chose her four classes because of how they connect with one another, not only on the land but also on the plate. After she started butchering animals, she wanted to know what they ate. When she started to study the grasses animals grazed on, she discovered that invasive species could be fermented. One interest led to the next. She says the best way to learn about food systems starts with being curious and asking questions like “I wonder what that animal ate.” “I wonder what plants are edible on this trail.”

As Anna butchered the beef, carefully cutting between each rib bone, she told stories of some of the people she’s met on her food journey: an enthusiastic farmer in central Montana who is building an underground citrus farm; first-generation bison ranchers in the Bridgers; mushroom hunters, wine makers, bread bakers, and more. These people are not just her suppliers, she explains, “These people have become my friends.”

The theme of relationships spread around the kitchen as we told stories of foraging and canning, epic elk hunts in the Missouri Breaks, and secret morel spots. None of us had the same food history, but we found commonality in curiosity.

We dug out the fire pit from the snow and prepped a fire for the steak. Looking up at the foothills around us, we discussed nearby cattle and bison ranches, what animals would be grazing when, and what they would eat. While Anna has studied food systems around the world, environmental issues, diet trends, nutrition, and more, what has stuck with her all these years is a system of farming called regenerative agriculture. As opposed to merely sustainable agriculture, regenerative works to take active steps to restore the land, which in turn restores the flora and fauna, and then our own bodies as we consume food.

“We need to do more than just ‘sustain,’” she says. “Think of it like a relationship: if someone asked you, ‘How are things with your significant other?’ and you said, ‘We’re sustaining,’ they would assume things weren’t great.”

One interest led to the next. Anna Borgman says the best way to learn about food systems starts with being curious and asking questions like “I wonder what that animal ate.” “I wonder what plants are edible on this trail.”

Anna has devoted her life to better understanding food systems— both how the land works, and how social justice (or injustice) impacts people’s food choices and health. She believes that major systemic change needs to happen, such as better support for small-scale farmers, and working to eliminate food deserts. However, Anna says nearly everything with a caveat: on one hand it seems so easy to buy local food, or research better ag practices, but she says, “It’s a huge privilege.” It takes time to research, it costs a lot more to shop for local meat or eggs, it can be nearly impossible for someone without a vehicle to leisurely visit a farm.

While our winter picnic was a group effort, it was by no means inexpensive. And it took weeks of planning to find local ingredients. We were very privileged to have flexible jobs that allowed us to afford quality food and gather together at a beautiful home in the mountains to discuss food systems. The afternoon was not typical or reflective of how most people interact with their food. There are still many hurdles to food equality.

Anna aims to be a resource in the community, someone who is approachable and always willing to learn. If learning about local food systems seems intimidating, which it can be, she says to start small. Find a farmers market or grocery store that sells local items. Look at the packaging, take note of where it is from, who grew it or made it. The next time you visit, ask a question to the grocery clerk, or even approach a farmer or rancher. Ask how they got started farming, or why they plant/ raise that particular item. One question will lead to the next, and a relationship will begin.

Most importantly, stresses Anna, find a place of peace and enjoyment with your food. Our shopping habits will never be perfect, but we can shape the food systems we want to see one question at a time, one bite at a time.