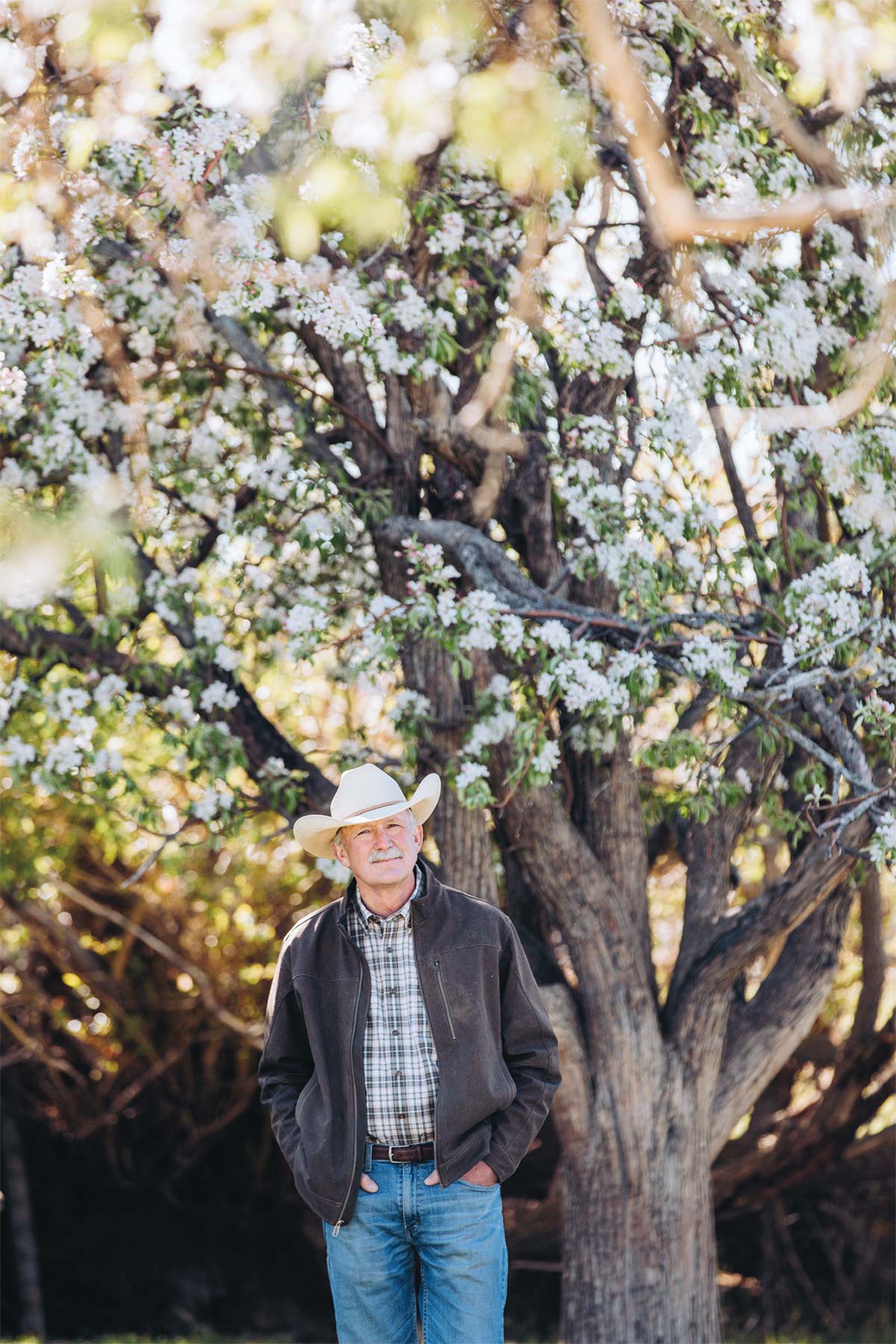

Katrina Mendrey, the orchard program manager at MSU’s Western Agricultural Research Center, collects bud wood from an old orchard in

the Ruby Valley.

Bìleìlitshìa, the Stinking Water, the Passamari, the Ruby Valley. This high mountain desert ringed by mountains carries many names and many stories. But this isn’t a story about the valley, exactly. This is a story about apples.

A HERITAGE

This is a story about a fruit tree that spread along the Silk Road from the mountains of Kazakhstan into the empires of Europe. Carried across the Atlantic as seeds, seedlings, and grafted trees and planted on the North American continent wherever settlers turned over soil and set down roots, apples spread.

Along the Bìleìlitshìa, in the Ruby Valley west of Ennis, apples arrived by the second half of the nineteenth century. There are several reports of orchards in the Ruby by the late 1860s, with hundreds of trees each. A letter to the editor in the Montana Post on August 18, 1866, commented on the health of a Mr. Brundy’s large fruit trees. Other references cite the plantings of a man by the name of John Redfern, but today evidence of these rumored orchards is scant. Mostly, there are old and gnarled trees next to ranches and along old irrigation canals.

Les Gilman, who grew up in the Ruby Valley and is executive director of the Ruby Habitat Foundation, doesn’t think there was any one commercial orchard planted by Redfern. Rather, he imagines Redfern going homestead to homestead, helping settlers plant apples for their fresh fruit and juice. “We have an old orchard on our family ranch,” he says. “We used to can gallons and gallons of the cider and have it for fruit juice in the mornings year-round.”

Agriculture is key to keeping local communities viable, not only from the economic perspective but also from the social perspective. —Les Gilman, Ruby Habitat Foundation

Whatever the history and fate of those rumored orchards, all that remains in the Ruby Valley of those turn-of- the-century plantings are trees, gathered around the sites of old homesteads. There’s one up California Creek, standing shoulder to shoulder with 8-foot sage. Another few are at the Gilman family ranch. Another four are down along the Ruby River.

Though only a few trees remain, the Ruby Valley has what Katrina Mendrey considers to be excellent examples of heritage orchards. Mendrey is the orchard program manager at MSU’s Western Agricultural Research Center in Corvallis. In this position, with the help of retired U.S. Forest Service historian Mary Williams, she has compiled historical references to apples in the state between 1840 and 1940— approximately one hundred different cultivars of apple were planted across Montana between 1865 and 1902— and she’s surveyed heritage orchards aroud the state.

These are trees that have withstood over a century of the Ruby Valley’s harsh, high-elevation climate and are still producing apples. When Mendrey sees these trees, she sees apples that may hold the key to successful orchards around Montana—not just in the relatively mild climate of Montana’s apple belt, the Bitterroot Valley, where most of the state’s apples have historically been grown. These old homestead trees are clearly well-adapted to the arid Montana climate and soil. But they are also reaching the end of their lifespan.

“If we want to keep these trees going, we have to propagate them,” Mendrey says with some urgency over the phone in late June. She oversees the Montana Heritage Orchard Program, the goal of which is to preserve Montana’s fruit production history and the genetic diversity of fruits that have historically grown well in the Montana climate.

HOPE FOR GENERATIONS

Gilman has worked at the Ruby Habitat Foundation for nineteen years, assisting with the operation of the 1,100-acre ranch property in the heart of the Ruby Valley. The ranch was originally purchased by Craig and Martha Woodson, who came from the newspaper business in Texas in 1992 and bought the property for recreational purposes.

“Craig Woodson became passionate about the land and its capabilities,” Gilman says. “He became interested in every square inch of the property.” The owner wanted the ranch to stay intact forever, and he wanted it to be useful to the Ruby Valley community. To that end, the Woodson family partnered with Montana Land Reliance to create the Ruby Habitat Foundation in 2002, to manage the property in perpetuity.

“Agriculture is key to keeping local communities viable, not only from the economic perspective but also from the social perspective,” Gilman says. “But agriculture, wildlife, and recreation are competing uses. They may have some symbiotic benefit, but ultimately they compete for the same resources.” The ambitious goal of the Ruby Habitat Foundation, as Gilman describes it, is to find the elusive middle point, where agriculture, wildlife, and recreation can coexist.

Dave Delisi, the foundation’s outreach coordinator, thinks they have already made two valuable contributions to the local ranching community: They’ve increased no-till farming in the valley, after acquiring a no-till seed drill that allows seeds to be planted without fully turning over the soil (this process aids in carbon sequestration; see page 7 to learn more), and they’ve increased awareness about ways landscape conservation and agriculture can work together.

It’s insane to try to grow apples. Every apple you eat is a miracle. —Dave Delisi, Ruby Habitat Foundation

Delisi and Gilman hope that a newly planted experimental heritage orchard will also contribute to the local community. “We’re wondering if apples can be a viable cash crop in the Ruby Valley,” Gilman says. He was inspired in 2016 when he first heard about the nascent Montana Heritage Orchard Program started at MSU by Toby Day and Brent Sarchet. Gilman knew of a bunch of old trees in the Ruby Valley; he wanted to know what the apples were and what their history had been. But he also knew the trees were old, and he wanted to figure out how to keep them going.

In 2019, Gilman and Delisi participated in one of Mendrey’s grafting workshops held at the research station in Corvallis. The following summer, they planted two hundred thirty rootstock seedlings in a 1-acre test orchard on the foundation’s property. In August 2020, they grafted scion—bud wood collected from ten known apple varieties and several variety mysteries from around the Ruby—onto the rootstock.

The orchard plot is on a limestone bench to the west of the Ruby River, adjacent to an experimental field of sainfoin, a European perennial that is less likely than other legumes to cause gastrointestinal bloat in cattle. The plot is surrounded by an 8-foot deer fence. An automatic solar timer controls a valve allowing gravity-fed irrigation water from an old passive irrigation channel fed by the Ruby Dam to sprinkle the orchard. Dwarf rootstock trees are planted in nine rows of twenty. An additional two rows of standard apple trees and five plum trees grow alongside. Extra trees line the front of the orchard in gallon pots.

An orchard started from scratch is a tender thing. To reduce competition for water, all the grasses were removed prior to planting rootstock, and the plot was fertilized with cow manure. In June 2020, the rootstock plants stood no more than 2 feet high in the brown dirt, leafing out a dozen tender green leaves, two hundred thirty individual shoots of hope.

The early summer was hot and dry. Weeds were growing and Gilman and Delisi worried about water competition. In July 2020, they decided to do a light herbicide spray between the rows. They tried to protect the apple seedlings by covering each one individually with trash bags. But one year later, most of the young trees showed evidence of herbicide damage. At the beginning of this summer, only some twenty grafts were fully leafed out.

Time will tell their true fate, but as cooler weather descended upon the valley this fall, nearly two hundred of the little trees looked like they’d survive.

“Part of our mission is to conduct agricultural experiments to inform the public what to do—or what not to do,” Delisi says wryly. “We’ve learned a valuable lesson for others trying to start heritage orchards: Don’t spray early on.”

When the Ruby Habitat Foundation first decided to plant a heritage orchard, Delisi read a two-hundred-page book about all of the potential issues an orchardist could face: irrigation, fertility, coddling moth, fire blight, voles, pocket gophers, and other small vertebrates. “It’s insane to try to grow apples. Every apple you eat is a miracle,” Delisi says. “[But] to me, it’s full of hope, this orchard. We’re doing all of this for future generations, on a wing and a prayer.”

Even in the face of a novel’s worth of troubles, for the last one hundred years apple trees have fruited in the Ruby Valley, year after year. And perhaps, one hundred years from now, up on that limestone bench above the river, an old orchard will bloom in May. Come fall, when the first snow creeps onto the encircling mountains, the fragrance of ripe rubies from Kazakhstan will perfume the Bìleìlitshìa, the Stinking Water, the Passamari, the Ruby Valley.