Freshly harvested produce from local and regional sources, like what’s found at the Bozeman farmers markets, contains some of the highest levels of healthy nutrients and phytochemicals. Photo by Lynn Donaldson.

It’s not so mysterious after all

Nicole Masters digs her shovel into a field in southeastern Montana. Reaching down, she pulls up a sizable handful of soil. “You can tell by the root structure— whether it’s shallow or deep—the kind of grazing that’s being done on a landscape,” she says.

We’ve all heard the phrase “you are what you eat,” in relation to health and nutrition. First coined in 1826 by Jean Anthelme Brillat- Savarin in his book The Physiology of Taste, he wrote, “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are.” The idea that the food we consume has a direct influence on our health has been a hot topic ever since, but these days it’s much more complex than eating your fruits and veggies.

UNDERSTANDING SOIL HEALTH

In an analysis of USDA nutrient data, biochemist Dr. Donald Davis of the University of Texas shows that over the past fifty years, the amount of protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, riboflavin, and vitamin C, along with other micro- and phytonutrients in conventionally grown fruits and vegetables, has declined significantly. And it’s not just crops that are less nutritious than previous harvests: Modern agriculture and livestock practices have led to the degradation of landscapes and a lack of essential nutrients in the livestock raised on them.

Masters, an agroecologist living in New Zealand and author of the book For the Love of Soil: Strategies to Regenerate Our Food Production Systems, says we need to take it a step further when thinking about the healthiest foods to fuel our families. “It’s not just ‘you are what you eat’ anymore, it’s ‘you are what your food eats,’ and that means taking a hard look at soil health.”

The good news is that soil is resilient. “In places that have experienced 140-plus years of soil degradation due to modern agriculture practices, we are seeing striking results in repairing the health of the soil in three to seven years,” Masters says. By focusing on agricultural techniques like regenerative farming, rotational grazing, and eliminating the use of chemicals altogether, it’s possible to repair soil health, and in turn see higher levels of nutrients in the food we cultivate.

Masters focuses on the details—the fungi and bacteria, and how they communicate and interact below our feet. She says soil health is something often overlooked by farmers and ranchers, consumers, and policy makers.

CROP QUALITY

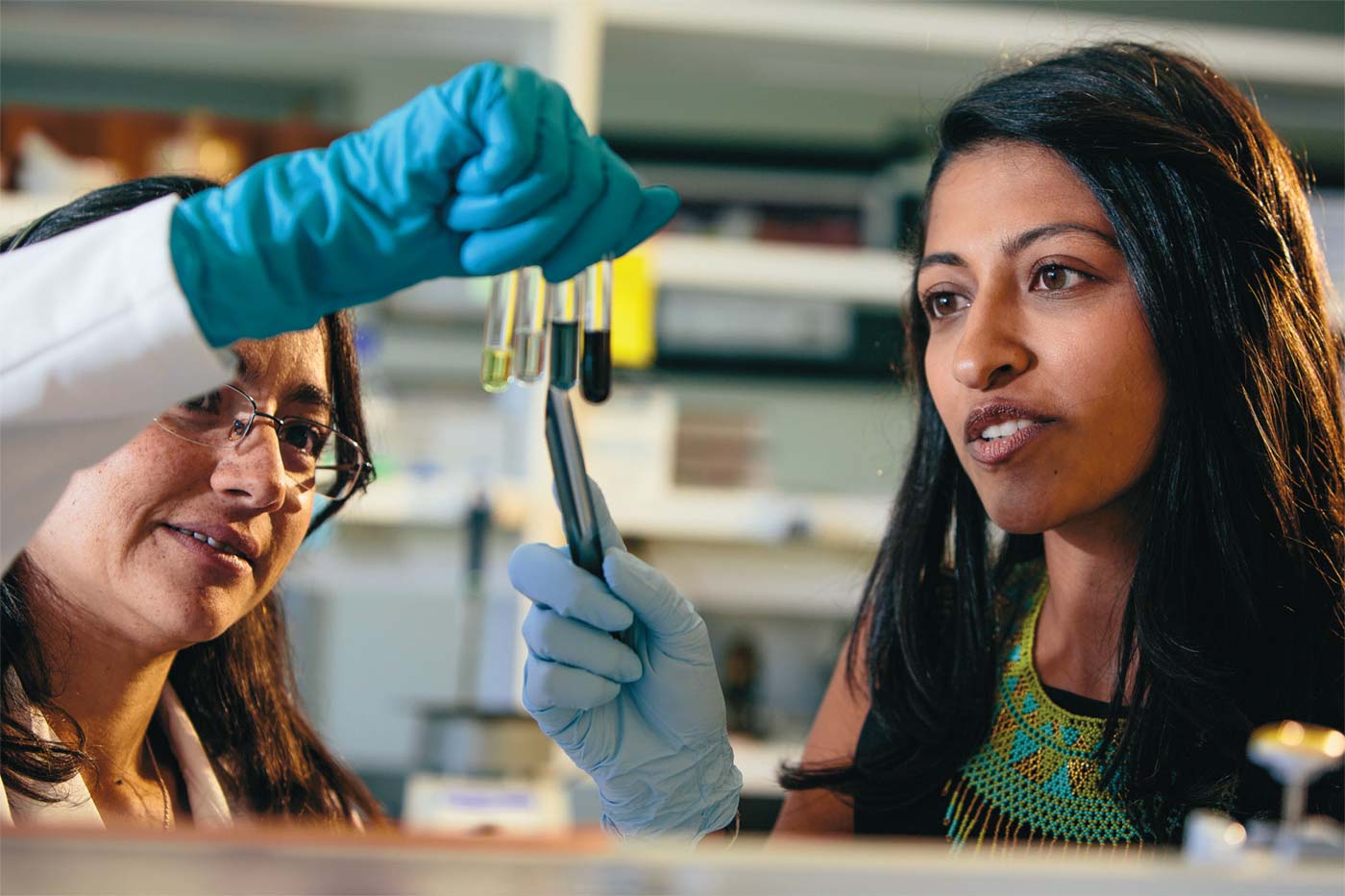

Ethnobotanist Dr. Selena Ahmed takes a broader view of the vanishing nutrients dilemma, but she agrees that it all starts with soil. In 2013 Ahmed moved to Western Montana from Boston to work in MSU’s interdisciplinary food systems program. Fascinated by how humans interact with the environment, she examines how various farming practices impact biodiversity and crop quality in the context of global change and the implications for farmer livelihoods.

“Food provides a critical lens in which to examine human interactions with the environment—and touches upon numerous societal challenges in terms of ecology, culture, socio-economics, equity, and health,” she says.

In between caring for her one-year-old and teaching at the university, she works at both the regional and international level to identify solutions across the food system that support human and planetary well-being. She specifically focuses on crop quality and linking the food production and consumption sides of food systems.

Her research has taken her around the world, from Venezuela to the Tibetan Plateau—a landscape that reminds her of Western Montana—studying traditional ecological knowledge in indigenous and rural communities. Currently, she is collaborating on studies in diverse regions to measure how climate change is impacting crop quality of tea, maple syrup, and fruit.

She says it’s not just modern agriculture, but also the increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that’s impacting the concentrations of micronutrients, minerals, and phytochemicals linked to crop quality.

“Research highlights that the carbon dioxide fertilization effect linked to climate change contributes to the dilution effect, with a decrease in nutrient concentrations of zinc, iron, and protein in crops. Factors linked to climate change can result in both increases and decreases of up to fifty percent in phytochemicals that contribute to the health-protective properties of crops for human consumption,” she says.

In the past, when scientists have looked at effects of climate change on food systems, they’ve focused on how rising temperatures could shift growing seasons, or how long droughts can damage harvests and cause food shortages.

According to a growing body of research, rising carbon dioxide levels are also making our food less nutritious.

Diversified farming systems that mimic natural ecosystems can enhance crop resilience and reduce the effects of climate change on crop quality. But Ahmed says more research is needed to better identify and understand agricultural solutions—and then we need the policy incentives for adopting them.

“Fresh, local, and seasonal produce from the farmers market overall has higher levels of antioxidant phytochemicals compared to the same type of produce from grocery stores that weren’t local.”

Finding Nutrient-Dense Foods

Together with her students and research associates at the Food Lab, Ahmed collects and analyzes the nutrient density of fruits and vegetables across forests, fields, farms, and grocery stores throughout Montana. “It is clear that not all produce is the same,” she says. “Tremendous variability exists based on environmental, genetic, management, storage, and preparation factors.”

In Montana, the Food Lab has found that wild-harvested edibles have among the highest levels of specific nutrients and phytochemicals, followed by freshly harvested local produce. “Fresh, local, and seasonal produce from the farmers market overall has higher levels of antioxidant phytochemicals compared to the same type of produce from grocery stores that weren’t local.”

It can be difficult as a consumer to navigate which foods are the healthiest. Ahmed’s strategy for finding the most nutrient-dense foods is to enjoy wild edibles when they are in season and preserve them for the winter months when nutrient-dense food is hard to come by. She also recommends focusing on local and seasonal produce, and getting to know some of the local farmers in your area and learning about their farming practices.

During the long winters in Montana, she recommends tapping into regional foods from places that have a longer growing season. When in doubt, she takes matters into her own hands. “I have a cherry tree in my backyard,” Ahmed says. “The cherries are too astringent to enjoy, so I infuse them with bitters and break them out in the middle of the winter when I need a hit of nutrient-dense phytochemicals.”

Both Masters and Ahmed are excited by the possibility of a Regenerative Organic Certified label, an add-on to the organic certification that recognizes practices that actively build soil health, conserve biodiversity, and sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

At the end of the day it’s not so much about the label as it is about the farming practices. Whether it’s produce or livestock, food grown on healthy landscapes without added chemicals or pesticides is higher in phenolic compounds, which have been linked to reduced risk of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases as well as multiple types of cancers.

On a local scale, one of the best things conscious consumers can do to make sure the food they buy is nutrient-dense is to support farms that follow a healthy agricultural-systems approach.

“We have tremendous power as consumers to influence the landscape through our purchasing decisions,” Ahmed says.

The more consumers understand the importance of seeking out food that is grown using these alternative farming and ranching methods—not only to benefit the environment but also for their own health—the closer we come to getting back our vanishing nutrients.