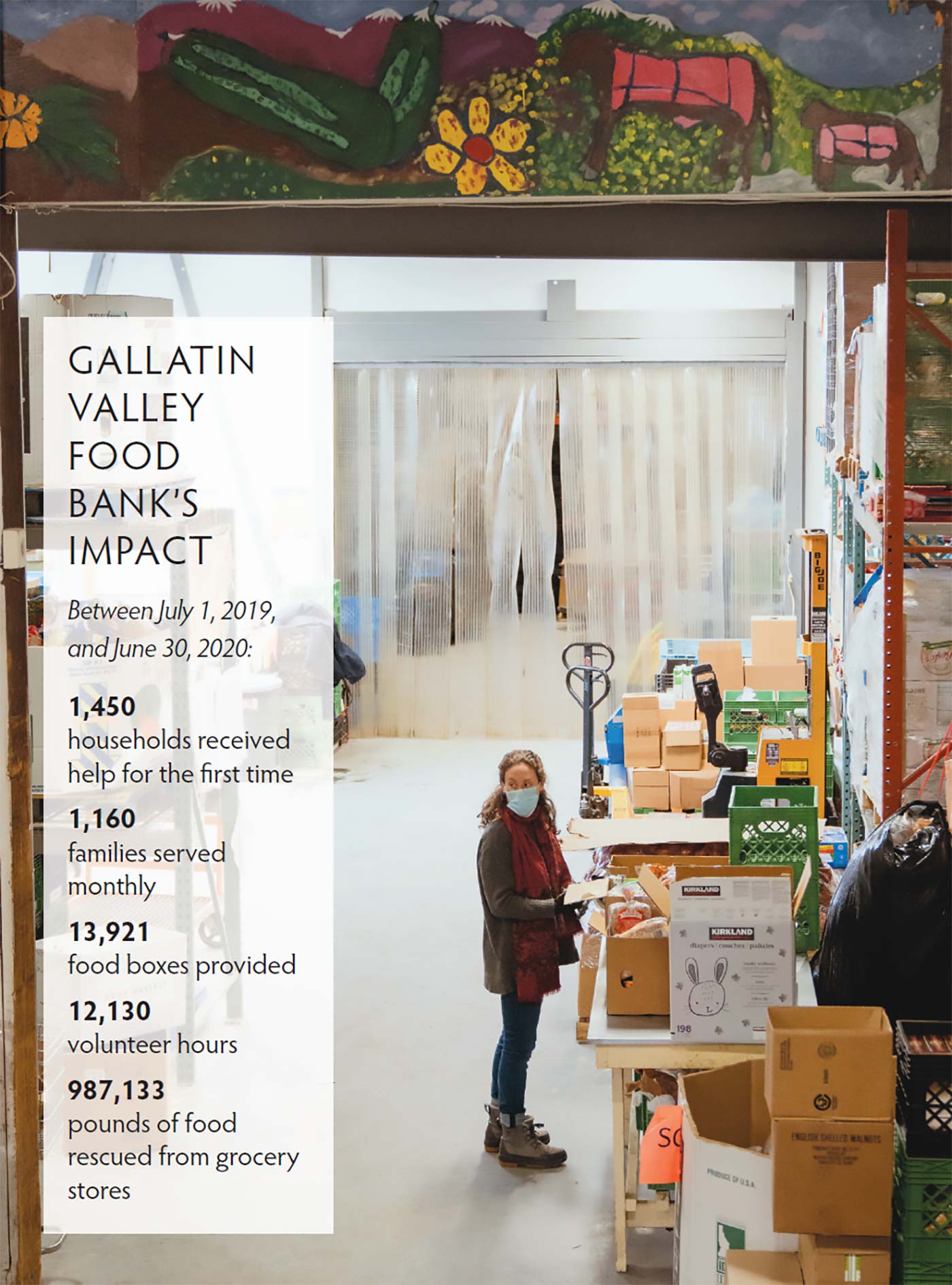

Laura Stonecipher, Gallatin Valley Food Bank programs manager, loads boxes of food into a car for delivery.

For an adaptable team, they adapted to the unimaginable

Nearly forty years after the Gallatin Valley Food Bank opened its doors on Mendenhall in 1982, the food pantry supplied emergency food assistance to an average of 1,160 households each month between July 2019 and June 2020—a single-month average more than double the 549 households they fed in their entire first year of operation. The cause: a rapidly growing community nearly held hostage at the advance of COVID.

The Gallatin Valley Food Bank (GVFB), like many of us, could not have predicted the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic. In the midst of a pandemic bound to significantly affect those that are food insecure, GVFB needed to figure out how to keep feeding our community safely, at a distance, while maintaining its reputation for being a crucial entry point. On March 17, 2020, it was “all hands on deck,” as Jill Holder, director of Human Resource Development Council’s (HRDC) Food and Nutrition Department, emphasizes to me during an all-too-familiar Zoom call.

ADJUSTMENT

Holder explains that to ensure a steady and reliable food supply to their customers, GVFB has three main ways of procuring food: rescuing food from local growers and businesses; accepting donated food from farmers, retailers, individuals, congregations, and government sources; and purchasing food with cash donations. Twenty percent of the pantry’s food budget is spent with local growers, while the remainder comes from the Montana Food Bank Network and local grocery stores. Of these three methods, food rescue is the most labor intensive. Staff members travel to local grocery stores with a refrigerated van and collect food that would otherwise have been discarded due to expiration dates, discounts, or an overage.

One year ago, GVFB set about on a three-part response to COVID, beginning with significantly reducing its food rescue efforts. The pantry staff also started bagging nonperishable food into pre-packaged boxes available through a new drive-through—a divergence from the self-select shopping model that customers were familiar with. The drive-through is open to all who need it, Monday through Friday 1–4pm. Instead of shopping inside the food bank, customers drive up and staff or volunteers bring out a cart with pre-packed boxes containing 80–90 pounds of food intended to last five days.

As the third step in its response, GVFB started to limit the number of people inside, including staff, volunteers, and customers. Volunteers are the backbone of GVFB operations and Holder says this was a difficult decision to make. Before the pandemic, there were fifteen to twenty volunteers each day, Monday through Friday. In mid-March, the food bank had to drop this number to seven volunteers. Since June 2020, they’ve been able to increase that number to ten each day.

According to HRDC—the Bozeman nonprofit that oversees GVFB—one in six children in Gallatin County struggles with food insecurity. As defined by the USDA, food insecurity is the inability to access nutritionally adequate food in a consistent and socially acceptable way. Knowing food insecurity affects children and the elderly the most, HRDC and GVFB have several programs to address chronic hunger among those most vulnerable: Healthy KidsPack, under which school-aged children receive meals to have over the weekend; Summer Meals, which makes healthy bagged lunches available to children during the summer months; and Senior Groceries, a monthly food delivery to older adults in the community.

Fork and Spoon, also a program of HRDC, is Montana’s first and only pay-what- you-can restaurant. They too adapted to fill a void. One year ago, they switched from dine-in supper to takeout meals, while continuing to deliver food to the warming center. They served 25,000 meals in 2020 and in the first two months of 2021, they averaged ninety-five meals a night.

“The pandemic has grounded people to basic needs.”

—Jill Holder

HELP

While HRDC was working to serve our community, the favor was returned. “The pandemic has grounded people to basic needs,” Holder explains. Though volunteers were reduced, a new group of volunteers emerged—servers and cooks helped when the restaurants closed. Normally at a low time of the fiscal year, donations to GVFB actually increased in March and April 2020. Furthermore, donors still made annual gifts in December. Spring food drives were canceled, like Bridger Bowl’s Carve Out Hunger and Spring for Food sponsored by First Security Bank and Cardinal Distributing Company. These organizations made financial contributions instead.

At Thanksgiving, the annual Huffing for Stuffing race went virtual and race fees were reduced. A mere 1,600 runners participated, down from the typical 3,000 to 4,000. Despite the decline in participation, Holder says, “We were just happy to make a profit in a year shaped by the pandemic.” In January, Root Cellar Foods partnered with GVFB in an effort to provide more fresh produce options to GVFB customers. Their online market offers an option to donate money to GVFB, funds from which are used by the pantry to provide local, fresh produce options to customers.

Our community stepped up in donations and labor to help those disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Thirty-six percent of donations to GVFB were less than $1,000 for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2019, and ending June 30, 2020, which means that individual contributions have a tremendous impact. Never think that you aren’t making a difference.

A NEW WAY AHEAD

Looking toward summer, GVFB hopes to do more face-to-face programming, if, Holder says, vaccination efforts continue and safety can be ensured. They will likely continue a part-time drive-through, while opening the pantry for self-choice pickup. Though the drive-through has been efficient, some things are lost. Customers lost the ability to self-select their food items because food boxes were prepared. Holder says that pre-pandemic, customers would come into the food bank, visit with staff , and go through an intake process that would help them in other areas.

“The great thing about the food bank is it ends up being an entry point for people,” Holder says, adding that sitting down face-to-face with someone means the staff can better get to know an individual and find the help they really need. “We have the unique ability, if we can visit with people, to do some problem solving. That’s one of the things that we feel strongly about and are missing right now: the ability to really sit down and visit with people.”

However, as Dara Fedrow, HRDC volunteer coordinator, explains, at the end of the day it’s about serving the greatest number of customers. “If we still need to limit the number of people inside of the store, that might really slow down how many people we can help a day,” she says. “We’ve gotten it down to be super-efficient. We can help so many people in a day because we just crank out a cart with a volunteer team and give it to the customer and they load it up. For the sake of helping as many people as possible right now, the drive-through is a really efficient way to do that.”

Food rescue efforts were back up to full capacity again in July 2020, and GVFB is back to seven full-time and two part-time crew members. However, they still have significantly reduced volunteer efforts. As the pandemic forced change, GVFB adapted and our community lent a helping hand—a bright spot in an otherwise dark year.

BOUNTY OF THE BRIDGERS

What began as a student project fed a community during a pandemic

In 2011, Stephanie Johnson, then an MSU undergraduate, conducted a survey modeled on one by the USDA that aims to determine national food insecurity. She wanted to ascertain the number of students on campus who were experiencing food insecurity. Over four years of research, Johnson found that about 33 percent of respondents identified as food insecure. Suddenly aware of the great need, the MSU Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Systems class, led by Professor Mary Stein, continued the investigation and worked to establish a food pantry on campus. The food pantry would have dual purposes: food rescue and supplying food.

After several years of work securing funding and establishing the university’s Food Resource Council, Stein and her students—with particular dedication from Teale Harden, who continued to advocate beyond her 2016 graduation, and Rachel Juel, who became a staff member for two years beginning in 2018—were successful in their efforts; Bounty of the Bridgers officially opened its doors in October 2017.

Since then, Bounty of the Bridgers has had two locations on the MSU campus. The first is a permanent pantry location in the basement of the Office of Health Advancement, open Wednesdays 11am–1pm and Thursdays 4–6pm. The second is a pop-up pantry located in the Family and Graduate Housing Community Center, open Saturdays noon–3pm. Both pantries have non-perishable items and produce and the Saturday pop-up offers food rescue items.

In March 2020, Bounty of the Bridgers switched from an indoor shopping model to appointment-only to increase safety. Customers were asked to sign up online to receive pre-packaged food boxes and the pantry halted Saturday food rescue efforts. As of December 2020, food rescue began again but online appointments remain.

Currently at the Saturday pop-up pantry, all food rescue items are placed on a table outside the Community Center. Juel, who is now living abroad, nostalgically recalls that the Saturday pop-up, pre-pandemic, was a true community event that became a kind of ritual for the graduate housing community, where folks could mingle and peruse food items akin to a farmers market. Marci Torres, director of MSU’s Office of Health Advancement, who has been in charge of the pantry during the pandemic, explains that now, however, food is pre-packaged, ready for grab-and-go.

At a time of need and in response to COVID, the university community stepped in to aid Bounty of the Bridgers. Torres says during the 2020 fall semester, staff and students volunteered to deliver pre-packaged food boxes when folks were quarantined. There were no delivery trucks—people used their personal vehicles to ensure that others were fed. “When you think about crises in our country, whenever something big happens, people tend to step up,” she says. “This has been no different.”

Sixty-five families used Bounty of the Bridgers in February 2020. When the pandemic hit, this climbed to eighty, where it remained through January 2021. It’s clear there is still a need and food insecurity on a university campus is an important issue to address. “We know nutrition is directly related to the ability of somebody to be successful, whether it’s in the classroom or at a job,” Torres says.

Similar to GVFB, Bounty of the Bridgers has been the beneficiary of several community donations, which contribute to improvements in pantry operations.

Donations also go toward purchasing food items from the Montana Food Bank Network. In January, the Mericos Foundation donated funds toward the purchase of a refrigerated truck that pantry staff and volunteers will use for the Saturday food rescue. Northwest Farm Credit Bureau doubled its annual donation in 2020, and Bounty of the Bridgers received CARES Act funding in order to purchase gift cards to Town & Country Foods that were given to students in need.