Glassblowing Shop in Livingston Spreads Light and Color

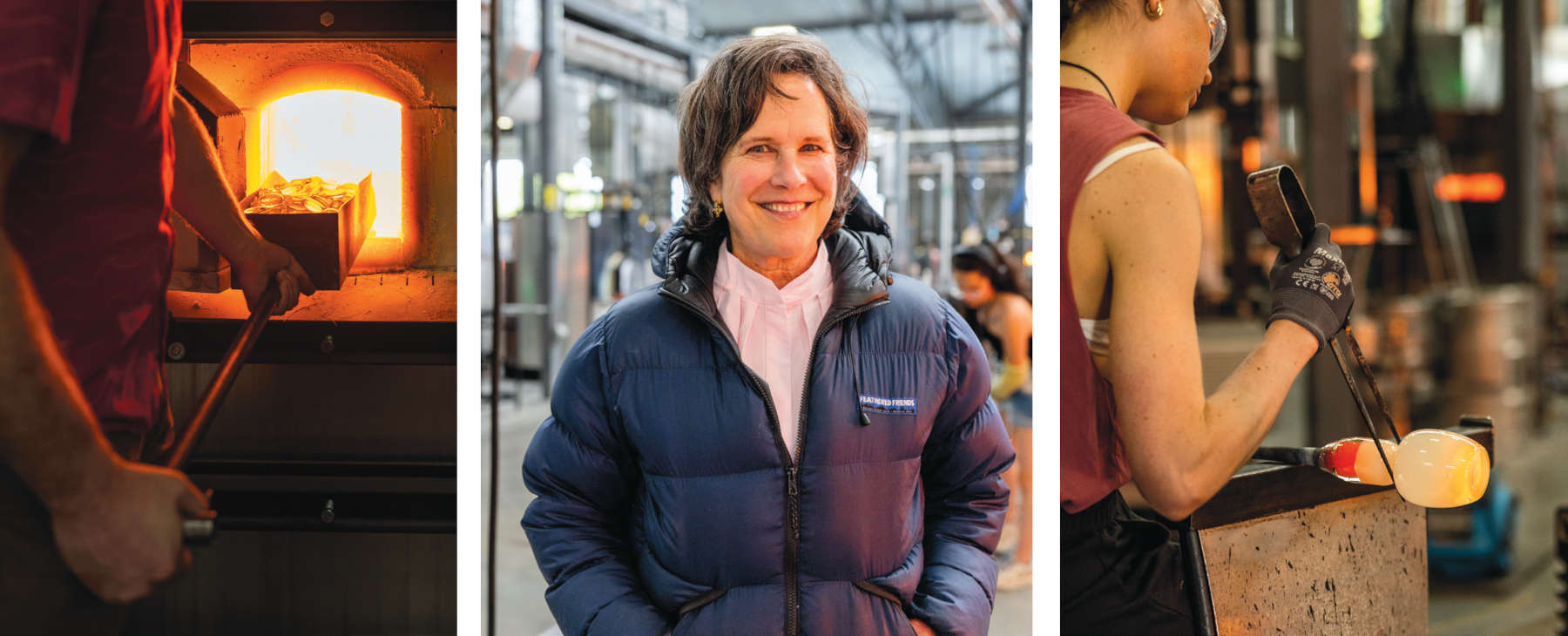

In the Bozeman area, it’s quite rare for a large piece of land advertised as a development opportunity to remain undeveloped when it sells. Even more unusual in Montana is the transformation of an equestrian center into a glassblowing workshop. About three years ago, along a five-mile stretch of the Yellowstone River just east of downtown Livingston, Lee and Peter Rhodes purchased the former Heart K Ranch and are stewarding it as open space. And as a part of the property’s newest chapter, the glassware company glassybaby (never with a capital G) opened its newest workshop—or hot shop—in what was formerly the ranch’s arena, where the company recently celebrated its first year of business in Montana.

In 1998, during an ordinary moment under extraordinary circumstances, Lee Rhodes lit a tea light and placed it into a hand-blown glass vessel she had been gifted. She was living in Seattle at that time, a young mother of three, and Rhodes was battling for her life with a diagnosis of progressive lung cancer and undergoing aggressive treatment. When the tea light illuminated the vibrant glass, Rhodes was overcome with a profound sense of hope and healing. This small flicker of light and color would come to symbolize and shape her future, both literally and figuratively.

It started small. In Seattle, the heart of glass art in the U.S., Rhodes found herself surrounded by a lively community of glass artists, studios, and museums. This made it relatively easy to find artisans to create similar cups. Rhodes initially hired artists to create these little cups to give as gifts so others might feel similar light in their lives. As time went on, Rhodes started selling these vessels out of her home garage. She was deeply connected to her experience of healing and was driven to make the path a bit easier for other cancer patients. In 2001, with this spirit of compassion and hope, glassybaby was born. Since then, the company has opened three hot shops—with a fourth opening later this year—and donated over $15 million to support hope and healing for people, animals, and the planet.

Rhodes might be better described as a visionary than a businesswoman. She openly acknowledges that, while she would prefer to donate all the profits, she must balance this desire with the need to support her team and sustain the business. She is dedicated to providing hope and financial support through beautiful works of art. With every purchase, a donation is made to various organizations. Now, glassybaby produces all its votives and drinkware in-house, with three hot shops in Seattle and a fourth in Livingston, where artists hand-blow all the glass. The company employes nearly 200 people and strives to cultivate positivity in the workplace.

Historically, glassblowing has been a male-dominated field, known for its complexity and high cost of entry. Opportunities to learn the craft were often limited, with few places to train and even fewer willing to pass down the tradition. The skill required either mentorship by an experienced artist or attending a specialized glassblowing school. Even then, finding work or building a career could be exceptionally challenging.

But glassybaby is seeking to change this dynamic with a comprehensive training program designed to bring newcomers up to speed for production work. With their move to Montana, glassybaby is not only providing a place to learn this art form in rural America but is also committed to investing in the local economy and enhancing the work-life environment. They offer the same wages and employee benefits in Livingston as they do in Seattle, reflecting their dedication to fair practices. Says Rhodes, “We didn’t move to Montana to do it cheaper.”

When the Livingston hot shop first opened, it started with a small team. A year later the shop has grown significantly—to 42 employees. The University of Montana Western, located in Dillon, is one of the few glass art schools in the Mountain West. Of the first 10 employees at glassybaby, three had come from this program.

Assistant Production Manager Nick Allen was introduced to glassblowing during a materials studies course while pursuing a degree in digital art in Iowa. He developed a passion for glassblowing and decided to move cross country and enroll in the glass program at the University of Montana Western. After graduating, he found his career options in glassblowing were quite limited, and working live demos on a cruise ship didn’t align with his aspirations. That’s when he discovered glassybaby’s hot shop in Montana.

The glassybaby team hopes to connect with young adults moving into the workforce, showing them there is a place to gain skills and make something with their hands. The business also encourages the community to visit the hot shop, where guests can watch artists melt and shape glass. The attached gift store is brimming with an abundance of color and soft glows from the candles illuminating each glassybaby on display. Amid the glass creations lining the shelves are plaques that share where money is donated from each purchase.

It’s easy to see the beauty in these small glass masterpieces. Art, in all its forms, uplifts the human experience, and glassybaby uses its art as a conduit for giving. Focused on supporting humans, caring for animals, and protecting the planet, the business’s list of beneficiaries includes both national and international organizations, such as the Rainforest Conservation Foundation, American Red Cross, Seattle Children’s Hospital, and Humane Society of the United States. Since locating to Montana, glassybaby has given $600,000 to support and uplift 45 local and state organizations, including Bridgercare, Gallatin Valley Land Trust, Western Native Voice, Big Sky Youth Empowerment, Farm to School of Park County, Livingston Food Resource Center, and FAST Blackfeet.

From the shadow of uncertainty that Rhodes faced all those years ago, one single flicker of light held the power to inspire multiple decades of beauty and generosity. May all find the courage to hold onto their hope as fiercely.