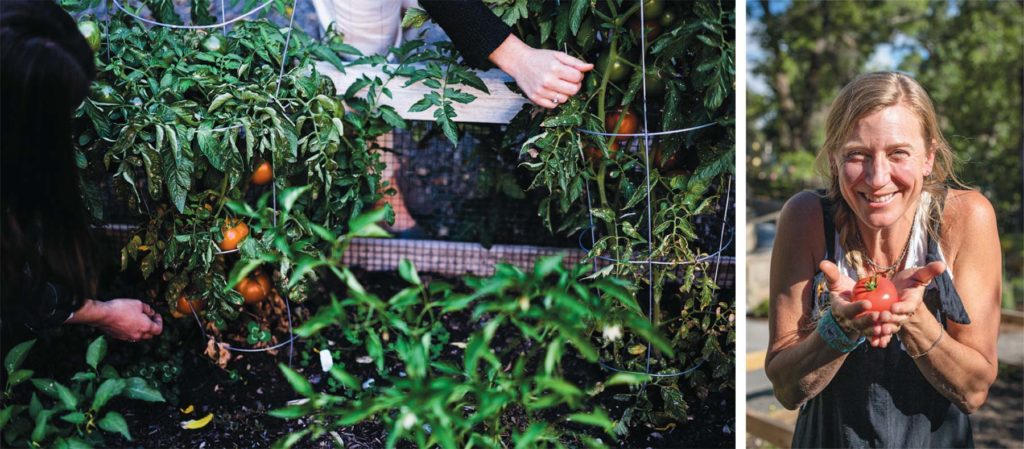

Carolyn Baker gardens in her greenhouse in Alder. Photo by Sara Gilman.

Growing, Grounding, and Connecting

Communing with the land can provide a profound sense of healing and nourishment, by showing us who we are and how deeply we are linked to the natural world around us. A lush patch of land enlivens us, especially when we’ve been there to witness its growth or even helped it along. Carolyn Baker and Margaret Stewart have made the healing aspects of nature part of their paths—connecting with the land, aligning their lives with its rhythms, and sharing with others how to do the same.

“We are having a back-to-the-land movement again, taking our healing and nourishment into our own hands.” —Carolyn Baker

RESTORING A CONNECTION

Carolyn Baker’s connection to the earth runs deep. She grew up in Great Falls and spent a lot of time alone in the woods. “When you become so comfortable somewhere, this becomes your safe place,” she says. “You feel the energy there. For me, being outside is so calming. It’s meditative. I feel that I’m from the earth, like all of us. I feel at home.”

Baker’s parents raised her around agriculture, instilling a strong connection to the land. “My family homesteaded in Choteau, where they dryland farmed, raising wheat and lots of flowers,” she says. “We always kept a garden. Working with plants is in my blood.”

Now, she works primarily as a wellness and life coach, using her connection to the land to help clients create and maintain long-term changes in mind-set and health. In addition to her training as a master gardener and garden coach, Baker earned a master’s degree in health and wellness life coaching from the International Coaching Foundation. She also holds a level II certification as a Reiki practitioner and a certification in meditation, mindfulness, and positive psychology from the School of Positive Transformation.

When her father passed away 20 years ago, after she had studied art and therapy at MSU and uprooted in order to travel, Baker picked up gardening again.

“My husband, Wayne, and I had just bought a house, and the house had gardens in terrible disrepair.” While rehabbing the garden, she found solace, peacefulness, and connection. “It kept depression at bay,” she says. “I was able to create a sense of calm and mindfulness there.”

Now, she helps clients do the same, using plants and gardening to improve mental and physical health. She works with a wide range of people, from children to the elderly to veterans and people struggling with addiction.

Baker shows people what they can grow to help their mental state. “For me it’s this beautiful fourfold power of planting, growing, caring, and consuming,” she says, adding that an important part of gardening is how it encourages awareness. “There’s this awareness of an external environment happening outside of yourself. We take in vitamin D, and we also release this tape we play in our brains—these habitual thought patterns—all while creating good energy. This helps a lot of people with anxiety, for instance. To care for something outside of themselves, and to get outside of what is making them anxious.”

Baker often creates vitamin profiles for her clients, identifying their specific dietary needs. Then, instead of telling them to go out and buy vitamins, she provides a list of foods they can eat and often grow themselves.

Currently, Baker is working with a high school senior who will soon head off to college. This client worries about food intake and how it will work at school, and also about anxiety. Baker is working with her on a window box that the client can cultivate while at university. “Taking care of a window box of greens gives purpose and nutrition, calms the nerves, and grants a sense of pride,” Baker says.

She is assisting another client with severe dementia, creating a nutrition regime to help her stay grounded and centered, and to slow the development of the dementia by helping her maintain myelin sheaths and retain what memories she has. “The culture around healing here in Montana is evolving really fast,” she says. “It is not just new people moving in—it’s also the fabric of these communities that is shifting in the way they regard the land, healing, and our relationship with it. We are having a back-to-the-land movement again, taking our healing and nourishment into our own hands.”

She encourages people new to gardening, or looking to learn how to improve their yields, to ask for help.

“Ask a neighbor, find a community garden, call a garden coach, or go to a library and check out books—that’s how I started,” she says. “Ask your neighbors. They know the climate and what to grow first. And then you can live your life feeling in tune and connected with them as well. The more you give in a garden, the more you get.”

“Stick some seeds in the ground and water them accordingly. It’s an experiment. Sometimes things don’t work out, but plants want to grow.” —Margaret Stewart

FULL-CIRCLE WELLNESS

Margaret Stewart has always loved gardens. She worked as a landscaper and in the restaurant industry, holding a position at the Farmer’s Daughters Cafe and working as a baker at Blackbird Kitchen. But in May of 2019, when she returned from a Grand Canyon rafting trip and learned the Eating Disorder Center of Montana was looking for a house manager and chef, she decided to shift gears and accept the position.

“I was at a point in my career where I wanted to use the skills I had developed to give back in some helpful fashion,” she says. “Creating meals in a restaurant or making a yard look pretty for a client is great, but I was craving something more meaningful.”

The EDCMT, founded in 2013, provides comprehensive treatment through in person, virtual outpatient, intensive outpatient, and day treatment programs. The Voss House is where the partial hospitalization program takes place, where patients are treated with structured, holistic services, from individual and group therapy to yoga and art classes. Th e patients, both men and women, come primarily from Montana and they range in age from 16 to 60.

At home, Stewart had a garden in the backyard that her two daughters, now ages 19 and 21, helped her tend. “The garden was a highlight of our home,” she says. “My kids loved helping me turn the soil and plant the seeds. The best part was watching them pick green beans, tomatoes, and strawberries off the vine. They loved the fresh food, and I didn’t mind if any of it made it to the kitchen.”

After taking the position with EDCMT, Stewart was inspired from the experience with her own home garden. Jeni Gochin, EDCMT clinical director, had installed two raised beds and expanded the available growing area, and Stewart planted them. Stewart then crafted daily meals based in part on the food she grew and invited patients to work with her in the garden and use the produce in the kitchen during weekly cooking classes. “In all my years working in the food industry, this was by far the most wonderful and meaningful experience,” Stewart says. “Cooking for people and providing good food is one way to show love. It has been a great full-circle experience.”

Recently, Stewart stepped away from her position with the Voss House to care for her father, but EDCMT is continuing the work Stewart began. Gochin says the gardens have a great impact on patients. “They are peaceful, and invoke the idea of nourishment and visual beauty, along with the notion of seasons coming and going,” she says.

Last year, during planting, one patient commented that she had never had the opportunity to cultivate and harvest her own food. Stewart thinks that the garden had a lasting eff ect and may inspire that client to develop one of her own. For this patient and others, Stewart is convinced that the act of growing, harvesting, and preparing food from a garden shows a full-circle relationship to food and our well-being.

She encourages people to try growing a garden. “Stick some seeds in the ground and water them accordingly. It’s an experiment. Sometimes things don’t work out, but plants want to grow. See what happens!”